Dalton’s last lynching occurred on September 6, 1936. The victim was Lon McCamy. Lon McCamy had up until recently been a dishwasher at the Hotel Dalton, which was a pretty good job for a black man in Dalton. African Americans weren’t allowed to work in the mills. He had lost that job and resorted to general labor. He was a yard man for a widow, Mrs. Eva McCamy. (“McCamy” was a common name in town.)

Mrs. McCamy’s family was well to do by local standards. Her husband passed away in January, 1936 after working for years as president of the local utility company. Her son, Carl, was a prominent attorney.

Mrs. Eva McCamy was the accuser. Late one Thursday night, she said that a black man entered her home and she screamed. Neighbors called the police.

The sheriff said Mrs. McCamy was touched on the shoulder and that Lon McCamy was seen running from the house. Neither of these things were true. The McCamy family said they would press charges for burglary, which indicated no touching had occurred. (It was still the law in Georgia that a black man entering the room of a white woman, without her permission could be presumed to be a rapist. I.e., if Lon McCamy had touched Mrs. McCamy, he would have been charged with attempted rape or assault, not burglary.)

Other stories survive as to what happened. Among the black community, it was remembered that a peeping-tom in black face was seen by Mrs. McCamy. She screamed, and the malfeasant ran away.

It was also rumored that the lonely widow was friendly with a black man who she would invite in the house. Late one Thursday night, this man was in the house and seen by a visitor. Mrs. McCamy did what she felt she had to do and screamed. The man ran from the house and left the property.

Lon McCamy had an arrest record for stealing a dollar out of a house. The evidence cited for the arrest consisted of the police chief’s statement that “McCamy is said to have been seen near the Barrett home during the afternoon.” After the lynching, it was said he was in the chain gang for an attempted attack on a white girl, but there are no country records of that.

Lon was arrested Friday morning after being trailed by bloodhounds from the Eva McCamy residence. Like his stealing of the dollar, he was the first black man that could be found. After the fact, neighbors said they saw him running in the dark.

When questioned, Lon McCamy said he was with his girlfriend. The police said his alibi didn’t check out. Lon McCamy was arrested without warrant Friday morning for “attempting to attack” Mrs. Carl McCamy. Mrs. McCamy’s son, said he would swear out a warranty for burglary.

Lon was taken to jail. News of the incident spread quickly. “Blood ran hot” as the saying went. The newspaper reported rumors that Lon McCamy would be lynched at 1 o’clock in the morning. Nonetheless, the sheriff went to sleep, the officers were dismissed and only one 59-year old man, John Pitts, a turnkey was left to watch Lon McCamy and the other prisoners.

The rumors of lynching were also recruiting calls for the mob. On Saturday evening, cars started to circle around the county jail. All told, about 30 cars made circles around the jail, each generally recognizable to the locals. This was not the Klan, as in earlier days, or bands of outlaws. These cars were full of local citizens attempting to follow the pattern set by those groups. Unlike the nightrider mobs, this one had little organization and didn’t rely on a standard group of men. It was large, uncoordinated and chaotic.

As the night went on, the men got out of the cars and surrounded the jail at the traditional time. The sheriff slept. In fact, he slept in the jail that housed McCamy.

According to several witnesses, about 150 men surrounded the jail early Sunday morning, around 2 a.m. Sheriff Bryant still slept. The men wore white handkerchiefs to cover their faces. Several of the mob entered the first floor of the jail, took the guard’s keys and hustled Lon McCamy away without hindrance. Pitts (the guard) retrieved the prison keys to lock the jail up again. He didn’t call for help or even wake up the sheriff; he simply went back to work.

Upon being interviewed, Pitts wouldn’t affirm the abduction, but then admitted he was “short one prisoner.” As he came to realize the gravity of the situation, Pitts’ story changed to say that he was held at gunpoint while his keys were seized. Pitts said he was unable to identify any member of the mob.

The traditional Lynch Law of the area, or the unwritten code of lynching, generally gave the victim the opportunity to confess and state his last words. This didn’t apply to McCamy. As Lon McCamy was taken from the jail, it was reported that he got away from the mob and ran. Lon McCamy could not have gotten away from 150 men surrounding the jail. Escape or not, four or five shots were fired into him in a vacant lot adjacent to the jail. This lot was in between the jail and the school for black children. The shots probably killed him. Sheriff Bryant, said he was finally awakened when he heard shots fired in the vacant lot. However, he couldn’t do much at this point as he said the mob departed almost immediately.

Lon McCamy was then taken, apparently dragged behind a car, to an old rock crusher site a short distance from the jail. The mob strung Lon McCamy to a telephone pole and fired more shots in him.

His body was left in the ditch by the rock crusher. That was where Sheriff Bryant found it four hours later in the early morning. It was reported that an investigation was initiated, but it wasn’t at that time.

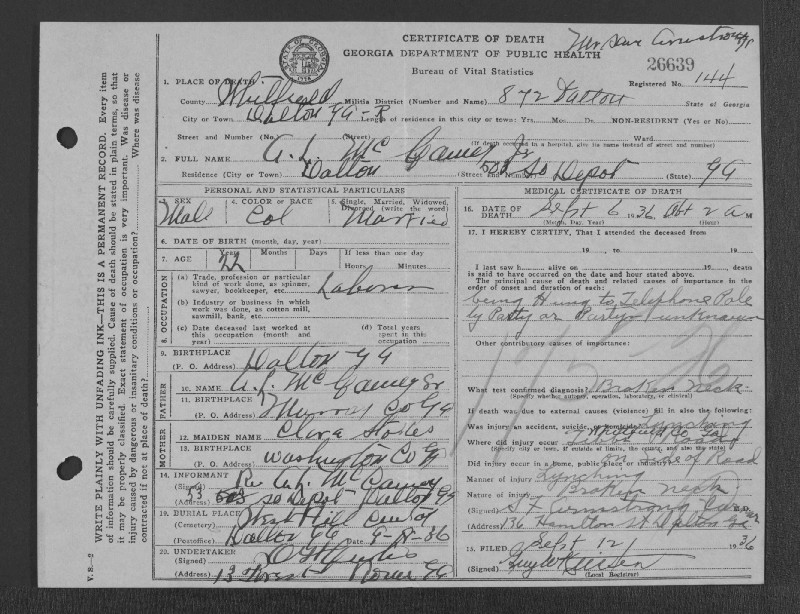

His family and friends eventually retrieved the body. His death certificate said he died of a broken neck after “being hung to telephone pole by party or parties unknown.” His family buried him in the Dalton cemetery.

According to one local woman’s recollection, Lon McCamy’s body was lain in his grave face down. A raw chicken egg was placed on the back of his neck and he was buried that way. As the egg rotted, so did the souls of the perpetrators of that evil. According to the legend, many of the perpetrators became sick afterwards and some killed themselves. The spiritual realm provided what little justice could be obtained.

The terror against McCamy made national news. The NAACP headquarters in New York placed its flag at half mast. Another flag hung below it with the words “A Man was Lynched Today.”

This particular lynching was seared into the collective memory of the black community. Many remember it to this day. Participants in the lynching spoke openly in the presence of black housekeepers and maids. Names could be remembered 80 years later.

The story was carried across the country, in the Atlanta papers, the Chattanooga papers and the New York Times. Awkwardly, neither of the Dalton weeklies carried a story. Instead, the Dalton News carried a few paragraphs on its letters page entitled “They Say” which went:

“Never before has the perniciousness of wagging tongues been demonstrated more thoroughly than by the happenings that have occurred in Dalton during the past seventy-two hours. The tension created by Saturday night’s occurrence put everyone, white and black, in such a nervous state of excitement we have all been ready to ‘jump out of our skins’ at the slightest noise or disturbance.”

The comment went on to reprove “Dame Rumor and Old Lady Gossip.” The Dalton Citizen carried a similar admonishment against spreading gossip and rumor.

The nominal investigation went nowhere. The sheriff’s son, a deputy, said “we’re up against a stone wall … can’t learn a thing” and that the city police were in the same position. “I doubt if we’ll ever learn who did it.”

The collective conscious of the town was one of slight embarrassment as shown by the lack of newspaper story and the buck-passing that went on. But the town moved on.

Bryant was an incompetent sheriff. But his actions during the lynching were less incompetence than complicity. Any member of the town would have known that a lynching was a likely event. Prisoners had been taken many times from the jail and were often moved to Rome or Atlanta in situations like this.

A few years later, Bryant was forced to resign from office after conviction for soliciting bribes. He was also known for taking hush money from bootleggers.

Judge C.C. Pittman, the local circuit court judge, addressed the lynching at the next term of court. This brought the first mention of it in the local newspaper. His condemnation instructed the grand jury to investigate, calling it murder and chastising the mob for failing to have faith in their own legal system. “Since the last term of this court, you have had a lynching in this county. A crowd of men who constituted themselves as guardians of the law and order in this community and for their purpose said: ‘We are the law, we are the order, we are the executioners. To Hell with officers, courts and jurors. You are too slow for us.”

“The most untrustworthy evidence known to law is hearsay, rumor, and propaganda.” Pittman instructed the grand jury to investigate the lynching which hadn’t yet been done. Judge Pittman also mentioned that it wasn’t his fault as judge that Lon McCamy had been released from the chain gang.

Whatever shame came from lynching an innocent man, and being humiliated in national newspapers, it didn’t last long. Townspeople would attempt another lynching a few months later.