Polk Mitchell and Charley Williams had a history. This history would unhappily lead to their fateful encounter on September 6, 1885, and both of their deaths.

Charley Williams was a black slater, a roofer. He was known as a good worker and was well regarded by prominent local builders.

Polk Mitchell was a white street car driver and former police officer. In the summer of 1885, things were looking up for him. After running off from his wife and children in Nashville, he’d gotten a position with Chattanooga’s police department. He moved his way up quickly to becoming assistant police chief to Chief James A. Allen.

Unhappily, that same summer Chattanooga’s police department blew up in scandal. Being second in command, Polk Mitchell was a big part of it. Chattanooga’s mayor had turned on his police chief and was calling for him to resign. The crux of the political crisis came down to money. The police department was supposed to file their cases in the city court, so the city could collect the fines. However, because of a personal connection, Chief Allen was having them filed with in the county courts.

Police officers were charging people just to rack up fines. Over a six month period, the police department cited 163 felony cases that were dismissed before trial for lack of evidence. The police department collected a fee of $3 to $4 for each dismissed case, but those cost the state about $20 each.

While the politicians cared about the money, the townsfolk white and black, saw another side of the corruption.

Chattanooga had an unofficial red light district and it was right next to the police headquarters. At the time, the city had about 100 prostitutes working. The mayor and authorities had made their peace with it; it couldn’t be stopped. However, that didn’t sit well with the citizens in general.

Chief Allen took advantage of this tension. He raided the brothels routinely, collecting fines, appeasing the citizenry. However, he let the madams go back to work as soon as the fine was paid, so as to collect again the next month.

Since the hypocrisy wasn’t worth fighting, many of the police officers became customers of the brothels, including Polk Mitchell.

In one instance, four officers headed by the chief went to raid a brothel. On the way one officer remarked that a particular policeman was likely there. The chief called off the raid to protect his officer. One officer with consent by the police department, paid two women, likely prostitutes, to leave town so as not to testify in a case.

The police initially weren’t allowed to wear guns. So they beat undesirables with their billy clubs.

In one instance, Polk Mitchell beat up a young roofer named Charley Williams. This may have been routine for Mitchell, but Williams remembered.

Then the police officers got their guns. In one of the rare reported instances, two officers approached a black man and woman. The officers drew their weapons on the couple and forced the couple at gunpoint to have sex for the officers’ amusement. Others were allowed to watch. The officers threatened the couple with imprisonment if they told anyone. Nonetheless, the couple complained to the police chief. The investigation found the officers not guilty of anything.

One of the local papers, headed by Alfred Ochs, diligently reported on this police corruption. In turn, Chief Allen beat up one of the paper’s reporters.

As to Polk Mitchell, he found that his wife’s cousin worked as a prostitute. He hired her and was caught kissing her out on the street. This was deemed too much and Mitchell was fired.

Polk Mitchell went back to working for the street car company.

Mule Drawn Street Car like the one Polk Mitchell Drove

On the afternoon of September 6, 1885, Mitchell stopped to pick up a passenger just past the corner of Fourth Street and Market. However, the man didn’t want to buy a fare. He only wanted to confront Mitchell for what Mitchell had done to him while on the police force. It was Charley Williams.

Williams was generally known as an industrious and peaceable man. He lived with his mother. Williams was described as “about 35 years of age, cinnamon colored, with a short growth of beard on his face.”

Williams stood on the side of the streetcar cursing Mitchell. Mitchell told him to get down and eventually forced him off after a ride of half a block at Sixth Street. Williams wasn’t through. From the street, he yelled to Mitchell, “I’ll get even with you son of a bitch!” He went home and got his pistol.

About an hour later, Mitchell was still driving the street car. He left the stable for the horse-drawn street cars, and headed toward the river with only one passenger now. At what was called Lookout switch, he stopped to let another car pass.

There was Williams, waiting at the stop.

Williams took a step towards Mitchell and Mitchell put his hand on Williams’ shoulder.

“Look here, Charley,” Michell warned. “You’d better leave me alone if you know what’s good for you.”

The View of the Mitchell-Williams Encounter Today

The encounter escalated. Mitchell reached for a metal transfer hook to hit Williams. Mitchell started to swing at Williams. Williams pulled a pistol and shot Mitchell two times. The first entered his chest and pierced his heart. Mitchell fell to the ground in convulsions and Williams shot him two more times. Williams then took off running.

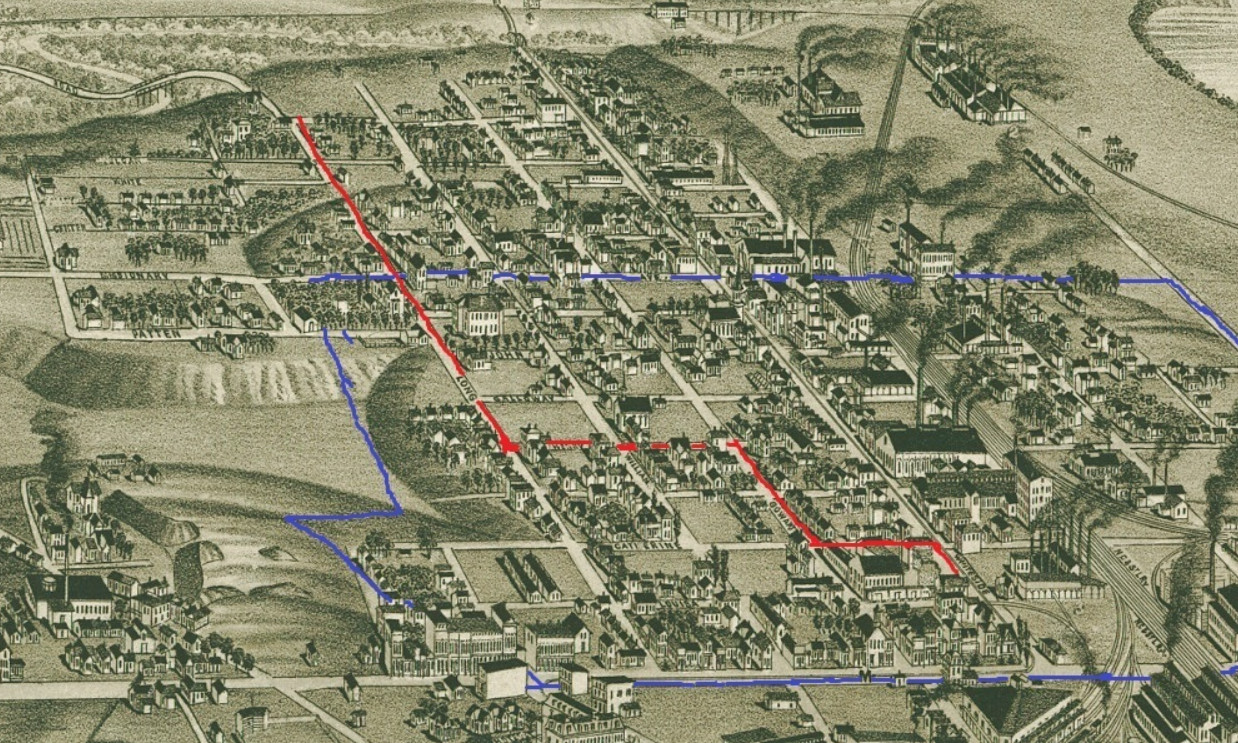

He ran from Catherine to Cowart Street. Then to Henry, then to Chattanooga Creek. (This is the Southside, near Jefferson Heights Park). He jumped in the creek and tried to hide in a clump of bushes on the far side.

The Red Line shows Williams attempt to flee. The Blue Line is the boundaries of the Fifth Ward.

Quite a few folks saw the shooting. Mitchell was turned over on the pavement, and a pillow was placed behind his head. He died in a few minutes. A crowd gathered. Shouts rose up of “Stop the murderer” and “Kill him” and “head him off!” People spoke of lynching.

Many ran after Williams, “a long line of fleeing men were seen, all shouting and yelling like mad men.” Police joined the chase. One particularly fast man with a shotgun gained on Williams and caught him in a cane patch on the far side of Chattanooga Creek.

Williams knew he was caught. “Don’t shoot, I surrender.”

Police arrived and took Williams into custody. The crowd of people watching were turning into the mob. The police had to move Williams quickly to save his life. They took him back across the creek and through the Fifth Ward. As they moved Williams, the mob increased. They cried “hang, hang, hang him.” Many had clubs and pistols and others had stones.

“Lynch him,” they cried. The mob grew to 500 strong as they reached Ninth Street (now MLK).

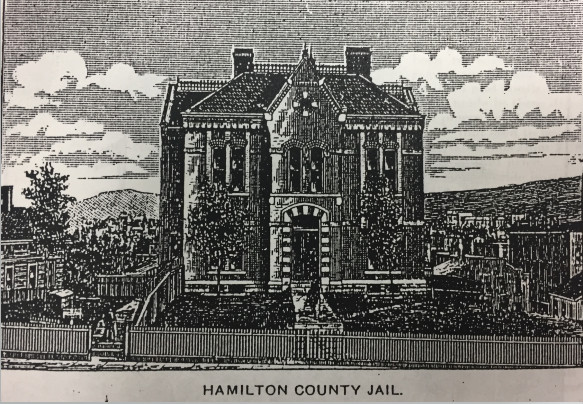

The police finally got Williams into the jail, and took him to the furthermost tier of the building, Cell No. 13. The crowd remained outside in strength, yelling itself hoarse. Williams was pushed in the cell and the door was slammed shut, waiting for the lynchers to find and destroy him.

They crowd outside the jail pressed on the fence.

Several people in the crowd went near hysterical when they saw a black man among them wearing a gun. The police confronted the man, took his gun. It turned out the man was a private detective named Charles Bird. He showed his papers allowing him to carry a pistol and he was released. The crowd calmed down.

Someone in the crowd began handing out pistols.

The sheriff tried to get in touch with the governor who was not in Nashville. The sheriff nonetheless called out two local militias to assist him. The soldiers, just boys, were not allowed bullets.

People in the crowd set fire to big wooden crates once darkness set in, but others put the fires out. Rumors flared of black militias moving in, setting fire to the city.

The Sheriff addressed the mob. He said the prisoner was secure and would face punishment in court. He asked that the crowd not the disgrace the city with violence and lynch law. The speech as well as the possibility of the militias had an effect. Many in the crowd dispersed, only to regroup in other parts of town.

A particularly large group met at the corner of Market and 9th Street and discussed the next steps toward Williams.

Meanwhile, the authorities held an inquest about Mitchell’s killing and brought in what witnesses could be found. Seven testified and the coroner’s jury gave a verdict that Mitchell met his death from pistol shots by Charles Williams. Three of the witnesses then visited the jail to identify Williams.

Mitchell’s body was laid out on a stretcher in the front room of his boarding house with his face uncovered. A crowd passed through lighted by the glow of dim oil lamps. “Poor Mitch! It was too bad he was shot like a dog.” “The hound ought to have been lynched as soon as he was captured.” This vigil went on until late in the evening.

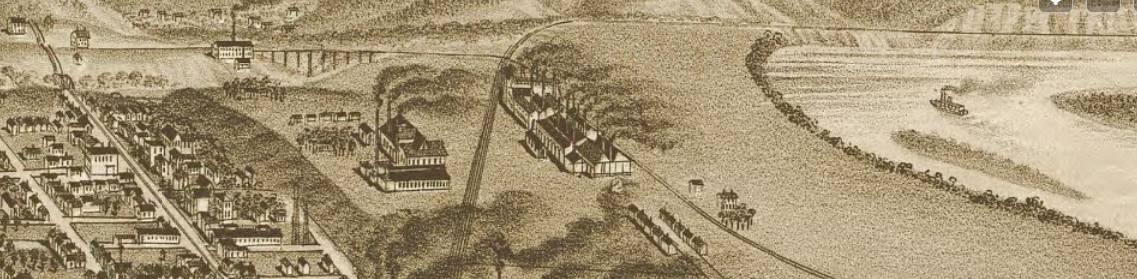

The Tredegar Works, marked as “2” near the bend in the river – where the mob first made its plan

A mob began growing at the Long Street bridge and South Tredegar works at 9PM. About 50 men were there as well as a newspaper reporter. Word spread of an attack on the jail. Speeches were given to work up the potential killers. Sheriff Pyott was an obstacle, although Sheriffs didn’t typically offer much resistance to a mob. The militia would also have to be dealt with. Although it didn’t seem like they would fire on their own people, the militia’s duty was to prevent killing the prisoner. However, the thought was that if they moved quickly, the authorities would step aside and they could take Williams and kill him.

Sheriff S.C. Pyott

Another meeting was held at 10PM at the Long Street bridge. About 150 were in attendance and the passion and rage solidified into a plan.

The militia arrived in town, and marched to the jail yard. A jailer was placed inside the cell with Williams. Several guards were placed at the windows of the jail.

Other rumors spread that the black citizens of town were organizing. It was reported that a delegation of prominent black citizens asked the sheriff to call out the “colored militia” but he refused.

Around 10:30PM, shouts were heard coming from the Fifth Ward. The shouts grew louder. The mob was coming to get Williams. Sheriff Pyott had the militia form a single line across the street in front of the jail gate. The soldiers stood with fixed bayonets in hopes of intimidating the mob. But their guns were empty. They had no authority to stop the citizen mob.

At 10:45PM the mob was in view of the jail marching on Seventh Street. Sheriff Pyott again addressed the crowd from the court house yard. His speech was met with jeers and curses this time. The area around the jail “was choked up with a mass of humanity.”

Many were wearing handkerchiefs over their face and carried shotguns and pistols. The leaders of the mob were said to be drunk.

“We know you have no authority from the Governor and can’t shoot.” The sheriff lied that the soldiers could shoot, going back and forth with the mob leader. This lasted about 30 minutes until the mob leaders were convinced the soldiers and deputies wouldn’t stop them.

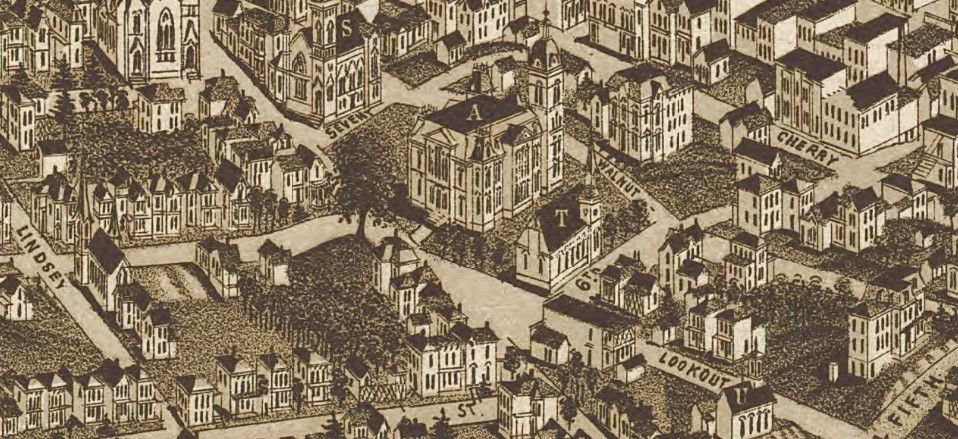

The courthouse is marked as “A” and the jail is across the street

The mob rushed the jail. In most jail lynchings, a handful of men simply went in the jail, took the keys and took the prisoner. Here, the jail was well fortified. The sheriff refused to turn over the keys. Some men were willing to take down the jail, others had to be coaxed into such a breach of civic duty. “Come on, come on!” cried those willing to storm the jail. The holdouts were accused of cowardice.

It took some doing to get into the jail. At 12:15 in the night, the mob finally succeeded in battering down the jail door. About 40 men went in and searched for Williams. The sheriff managed to get the lights turned off. The mob managed to get them back on.

They went floor to floor but couldn’t get into the cell area as the keys had been secreted with the sheriff. The lynchers worked with whatever tools they could find for 20 minutes to pry the door open an inch to the cell area. Finally, someone located Williams. He was on the second floor in Cell 13. Work renewed in getting to him. A newspaper reporter watched. He bizarrely reported on this rush to murder that, “it was perfectly marvelous that such good order prevailed.”

A dozen men battered the door while the others watched. No attempt was made any more to stop them, or even obtain the names of the lynchers. The battering went on for 30 more minutes until the first door lock was broken. Someone provided a sledgehammer to break the second lock. The door opened and the crowed poured into the corridor. The jailer stationed with Williams was allowed to leave unmolested. Williams was only protected by his cell door now as he watched his killers beat at his cell door with pick axes.

“We’ve got him!” they screamed as the killers entered the cell with Williams. Williams begged for mercy. He said “I’d like to see my mother.” A mob member shouted back “God damn you, you didn’t let Polk Mitchell see his mother!”

Williams was taken from his cell. He was moved down the corridor and up to the third story. There, an iron beam was built across the hallway in front of the entrance to the cells. Williams hands and feet were tied. A noose was made from mosquito netting and tossed over the iron beam. As Williams was pulled up, the netting broke. A rope was found and the mob tried again.

Williams was pulled up only about eight inches off the ground where he swung and began to strangle to death. After a few seconds he “began to writhe. His body would draw up and the muscles then contract. The contortions were horrible.” The crowd watched. “Soon his tongue protruded, froth gushed from his mouth, his eyeballs became distended and protruded from the sockets.” Then he died. A reporter noted the “glare from the half closed eyes which those who saw will never forget.”

Williams’ body hung another 30 minutes while whoever wanted to view it could pass by. Men and boys filed into the jail crushing each other, yelling and screaming at the dead man. A police officer turned the body around and around at the direction of the crowd.

Williams’ brother came by. The body was cut down about 1AM by the authorities. Another coroner’s jury was called finding that Williams met his death “at the hands of an unknown mob.”

Williams’ mother and father called for the body and it was sent to his home on Stone Fort.

At 1:30AM, the governor’s telegram came in authorizing an armed militia to defend the jail.

From the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama

Sources:

Chattanooga Times, September 9, 1885, September 10, 1885

Chattanooga Daily Commercial, September 8, 1885, September 9, 1885

New York Times, September 8, 1885

The Tennessean, September 7, 1885, September 11, 1885